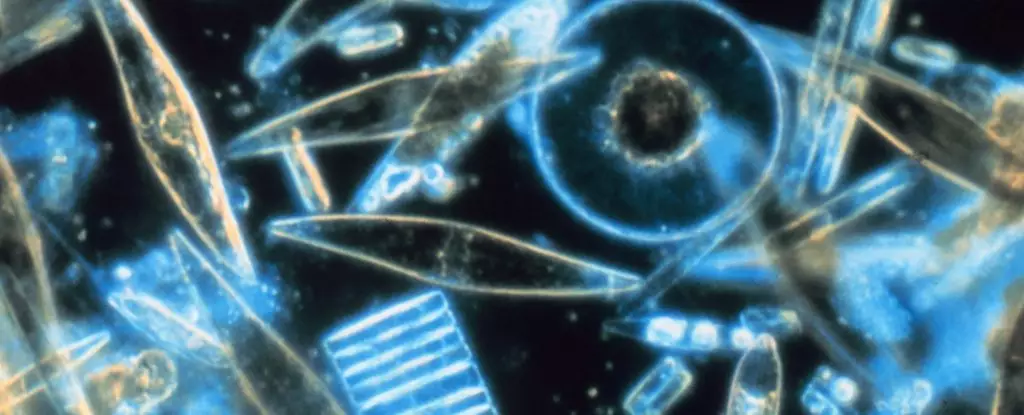

For decades, satellites have served as our eyes in the vast, often inaccessible ocean expanse, giving us a seemingly clear image of Earth’s complex marine ecosystems. Yet, recent discoveries cast doubt on the reliability of remote sensing data, especially in the icy realms of the Southern Ocean. What was once dismissed as mere optical illusions—bright, turquoise patches amidst dark, cold waters—is now revealing a deeper, unsettling story about our understanding of marine life and climate processes. These shimmering waters, thought to be dominated by coccolithophores—tiny sunbathing microorganisms with calcium carbonate shells—may, in reality, be largely shaped by diatoms, silica-shelled competitors. This revelation forces us to question the very accuracy of the tools we’ve relied on and underscores the urgent need for ground-truthing in climate science. It’s a stark reminder that we are still wrestling with incomplete knowledge, and that our assumptions about how the oceans sequester carbon and sustain life might be fundamentally flawed.

The Mirage of Remote Oceanography and Its Consequences

One of the most troubling aspects of this discovery is how long scientists depended on satellite imagery to interpret these enigmatic waters. Satellites paint a picture of vibrant, reflective patches purportedly rich in coccolithophores, fueling estimates that these microorganisms play a pivotal role in removing atmospheric carbon. If these assessments are based on misinterpretations—assuming brightness corresponds directly to coccolithophore abundance without accounting for diatoms—the implications are profound. Our understanding of the marine carbon cycle could be significantly skewed, leading to overestimations of the ocean’s capacity to absorb CO₂. This misapprehension has cascading effects: climate models, policy decisions, and international efforts to combat global warming all hinge on accurate data. To bolster our stewardship of the planet, we must recognize that remote sensing, while invaluable, is insufficient without robust, in-situ measurements. Otherwise, we risk building policies on speculative grounds—an intellectual peril with potentially catastrophic consequences.

Scientific Hubris and the Illusion of Certainty

The recent oceanographic expedition aboard the research vessel Roger Revelle exemplifies the importance—and limitations—of empirical science. Balancing satellite images with direct measurements reveals the complexity hidden beneath the surface. The discovery that the bright waters south of the great calcite belt are likely dominated by diatoms challenges long-held assumptions that these cold polar waters are inhospitable to coccolithophores. This not only redefines our understanding of microbial biogeography but also highlights the dangers of overconfidence in remote data interpretation. It reveals that dominant narratives—such as “these bright patches are caused by calcite-producing microorganisms”—may be gross oversimplifications. Such complacency hampers scientific progress, especially in the context of climate change, where accurate data is paramount. Pretending we fully understand these ecosystems without continuous, rigorous verification betrays a kind of intellectual arrogance that could hinder effective policy-making and scientific innovation.

Implications for Climate Science and Global Policy

At stake is more than just academic curiosity; it’s the reliability of global climate strategies. If the contributions of coccolithophores to carbon sequestration have been overstated due to misinterpretation, then the models that guide international climate commitments are flawed. Conversely, if diatoms—and their silica shells—are more influential in these regions than previously recognized, the dynamics of carbon cycling could shift. This emphasizes the critical need for adaptive, flexible models that incorporate new evidence. It also throws into stark relief the importance of investing in dedicated research that blends satellite technology with ship-based measurements, deep-sea sampling, and year-round monitoring. Without this multi-layered approach, our understanding remains superficial at best, risking poorly informed decisions that may fail to address the urgency of climate breakdown.

The Wake-Up Call for Scientific Humility and Adaptive Learning

Ultimately, the discovery that we may have been misidentifying the drivers behind the ocean’s reflective seas underscores a broader lesson: scientific knowledge is provisional, and humility must undergird our pursuit of truth. For too long, the scientific community has often placed faith in technology’s apparent objectivity, neglecting the importance of ground-truthing and acknowledging the limitations of remote observations. This realization is both humbling and invigorating. It propels us to embrace a more integrated, cautious, and humble approach to studying our planet—recognizing that nature’s complexity often defies simplistic explanations. As humanity faces unprecedented environmental challenges, this humility and commitment to continuous learning must become the foundation of our efforts—not a sign of weakness, but a testament to scientific integrity and a pathway toward more effective stewardship of Earth’s fragile ecosystems.

Leave a Reply